by RICK DANLEY // July 14, 2018

In place of the usual hello, Mike Hook, the veteran pawnbroker and manager of DM Past and Present, has a phrase prerecorded on his mobile phone, which he plays when a customer first enters his small Iola shop. The audio is of a woman’s voice, tinny, robotic — it’s the standard issue voice of Google Translate, in fact — and it’s one of the few ways remaining for Hook to sever, if only momentarily, the vast silence into which circumstance has plunged him.

CUSTOMER [enters store, sound of door chimes]: “Hello. Hot day, huh?”

MIKE [seated behind the counter, reaches for his phone, hits play]: “Sorry,” the automated voice intones, “I’m not trying to be rude but I lost my tongue to cancer a few weeks ago.”

CUSTOMER [she peers at Mike — his neck girdled by a tracheotomy collar, his hand dabbing at his lips with a cloth every several seconds because he’s lost the bulk of his salivary control — and she finds that she can no longer locate the perfect response]: “Oh,” she says. Or: “I’m sorry.”

HOOK, who was never a drinker and never a smoker, was stricken three years ago with an oral cancer, which, after laying dormant for a time, made a brutal point of returning 13 weeks ago. Doctors needed to operate, and fast. Hook, a gentle man with spectacles and a mop of thinning gray hair, was told prior to entering the operating room that the surgeon would likely only remove a very small, significantly affected area of his tongue. But when he awoke 12 hours later, it was to find that they’d taken the whole thing. He couldn’t speak, he couldn’t eat, he couldn’t drink. He still can’t. Of his former tongue, Hook says, they seized it by the root. He makes a slicing gesture with his hand: “Gone.”

HISTORICALLY, in the practice of writing, the easiest way of expressing speech on the page has been to employ what are called “dialogue tags” — the “he said” or “she said” that follows a line of conversation. But, in Hook’s case, the “he saids” are the hardest part.

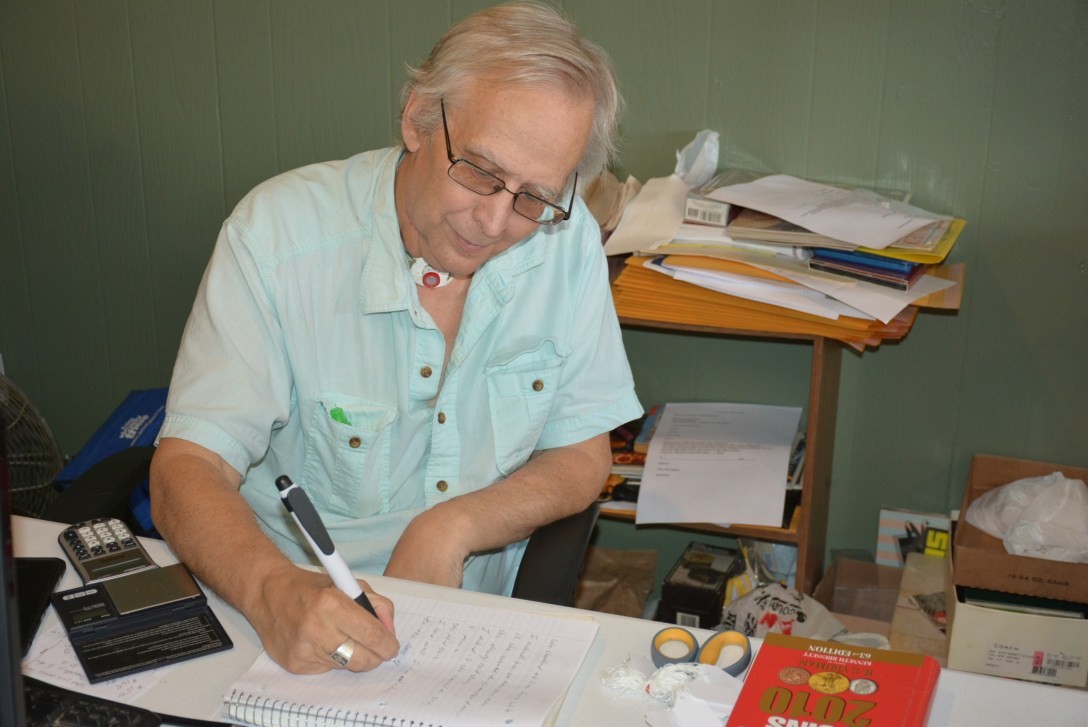

Hook currently has three ways of “saying” anything. He keeps a lined notebook and pen on his desk, which is his most frequent method for relaying his thoughts. He avoids the often unwieldy, Google-generated voice if he can help it. His preferred method still — born of a lifetime’s habit — is to try to vocalize his thoughts, slowly, carefully. To talk, in other words. But his success rate in this form is mixed at best. More often than not, Hook is asked to repeat himself, at which point he’ll drop again into the use of pen and paper.

It’s not impossible to understand a man without a tongue; it’s only very hard. It sounds like this: Press the tip of your own tongue firmly against your bottom row of teeth and hold it as rigidly in place as possible. Now, read the previous sentence out loud.

Hook has started a twice-weekly speech therapy program at Allen County Regional Hospital but it’s too early in the process to have registered much effect.

ANYWAY, Hook is and always has been a man more in the company of objects than people.

And given the slow foot traffic at DM Past and Present, Hook’s limited capacity for speech isn’t challenged too many times in a single day. Instead, his hours are spent, in the main, among the inanimate bric-a-brac of life, objects whose demands on Hook are — though each item has its own story — entirely non-verbal.

A very partial list of the items lining the walls of Hook’s Washington Avenue store would include: DVDs, mass market paperbacks, an automated steamer, rare coins, Harry Potter action figures, jewelry-making kits, Native American wolf decor, big and small toys, a signed photo of TV personality Steve Wilkos, plastic necklaces, cookbooks, artfully slumped rows of stuffed animals, crates of vintage LPs, decorative plates, commemorative whiskey bottles, ceramic angels, ceramic flowers, A&W Root Beer mugs, an enormous Sephrabrand chocolate fountain, cutting boards, a melancholy Emmett Kelly snow globe, a Pepsi soccer ball, a Pepsi Santa figurine, a Pepsi yard glass, collectible Barbies, a fur-collared flight jacket (think Tom Cruise’s cute torso in “Top Gun”), model cars, packets of beads and other necklace-making equipment, an antique bathroom scale, a 16-piece miniature tea set, a dinosaur diorama, a beginner’s metal detector, a microwave stand, soup mugs, dozens of $2 skeleton keys, brooches, bracelets, earrings, rings, circlets, tie pins, cufflinks, fossils, homemade cayenne pepper pills, bottles of moringa oleifera (good for arthritis, diabetes, and a lagging sex drive), comic books, baseball cards, old magazines, and more. Much more.

DM PAST AND PRESENT isn’t technically a pawnshop, however — it doesn’t offer loans, for example, and so doesn’t need to carry pawn insurance, which is cost prohibitive — but Mike Hook is, in his every fiber, a pawnbroker.

A Kansas City kid with a penchant for cast-off things, the teenage Hook found himself helplessly drawn into a nearby pawn shop. He kept up the habit until he was 21, kept it up, in fact, until his habit became his career.

I sat down with Hook last week in the bright front room of his shop, a pad of paper and a pen between us. I asked how he’d gotten started in the business. He wrote his answer in careful block letters: “I VISITED METRO PAWN A LOT WHEN I WAS YOUNG AND SOMEHOW I GOT BEHIND THE COUNTER AND BOOM I WAS A PAWNBROKER.”

Hook’s main interest as a young twenty-something was in silver coins. It remains his main interest today. Asked how he knows whether a coin or piece of metal is genuine, Hook retrieved from beneath his desk a small box containing six plastic dropper bottles, each container the size and shape of a food-coloring bottle, and each one containing a specific acid. “Testing kit,” said Hook.

“Do you check every metal item that comes through the front door?” I asked.

Mike dabbed at his lips. He spoke slowly. “Yes. I check it.”

He turns in police reports on most items he buys, too, especially when it comes to precious metal.

“And what percentage of pawnshop customers lie about the quality or provenance of what they’re giving you?” I asked.

“A lot.”

FROM METRO, Hook moved to another Kansas City institution, Smart Pawn. Eventually, Hook would go on to launch his own pawnshop, Mike’s Pawnshop, in Leavenworth. “But then I went through a divorce and the shop” — Hook makes another slicing motion with his hand: “gone.”

In time, Hook would find a place behind the counter at Alpha Pawn in Kansas City. And most recently, which is to say up until his latest surgery, Hook was a pawn manager at one of the largest pawn shops in the KC Metro area, Olathe Trading Post & Pawn, where the stock-in-trade was not the vintage Barbies and mock jewelry that walk through the door in Iola, but was, instead, more on the order of high-powered guns and diamond rings.

For Hook, the thrill of being a pawnbroker has to do with the flush of the unexpected, the everyday jolt of being surprised. “You just never know what’s going to come in the door,” he said. He took up his pen. “THE BIGGEST SINGLE PURCHASE AT OLATHE WAS $22,000. GOLD AND SILVER. BARS AND COINS.”

“Who has that much gold lying around?” I asked.

“THIS ONE HAD A HUSBAND DIE. SHE TOOK IT AROUND AND WE PAID HIGH. THEN WE SOLD IT TO THE REFINERY IN RIVERSIDE MISSOURI. ELEMETAL.”

THE PAWNBROKER’S reputation in popular culture is not an especially noble one. The broker in Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” (1866) — whose murder is the plot point around which the novel turns — is described as having “eyes that sparkle with malice.” Depictions have not improved much since then.

The pawnshop is that classic ornament of the urban nightscape; the neon sign, the barred windows, the desperate air. Pawnbrokers themselves are seen as hard men, men worn down by their daily commerce with ambitious hustlers, men who’ve had to harden themselves against the waves of sad cases that every day pour through their doors — the widow on her last nickel forced to hawk the family’s silver, the alcoholic selling off his kid’s bike for another couple of bottles.

So how to explain Hook’s gentle nature or the trail of kindnesses his customers have remarked upon over the years except to admit that there is variety in every profession, that there are such things as honest lawyers. Still, admits Hook, a jeweler’s eye and a healthy caution are essential traits in a broker’s toolkit.

“I HAD A GUY COME INTO ONE OF MY NEW PAWNBROKERS WITH 6 HIGH END GUITARS FOR $5,000 SO I CAME UP AND ASKED WHERE DID YOU GET THESE HE TOOK TOO LONG TO ANSWER SAID HIS GRANDFATHER DIED AND HE INHERITED THEM SO I TOLD THE NEW PAWNBROKER I WANTED A COPY OF THE DEATH CERTIFICATE AND THE COPY OF THE WILL THE NEW PAWNBROKER THOUGHT HE WAS A BIG SHOT AND… BOUGHT THEM BEHIND MY BACK”

“For $5,000?” I asked.

“Mm-hm,” said Hook. “5 DAYS LATER PLATTE CITY POLICE PICKED THEM UP STOLEN.”

The water and light for any budding pawnbroker, explained Hook, is simple: “BEING ABLE TO READ PEOPLE AND BEING ABLE TO VALUE THINGS.”

IT’S UNCLEAR to Hook just how long he’ll keep his Iola shop open. It’s hard on his body, which is still in the process of recovering. And he has to close the shop more days than he’d like, because of doctor’s appointments. “I HATE MISSING SO MUCH AND NOT BEING ABLE TO TAKE CARE OF MY CUSTOMERS,” wrote Hook. “I HAVE CUSTOMERS COME HERE FROM A LONG WAYS AWAY AND THEN I’M CLOSED.” He looked up from his note pad. “I hate that.”

Hook lives with his wife in Garnett. “It’s been hard on her,” he admitted. “See, I almost died.”

Hook can no longer eat or drink orally. He has a feeding tube that extends from an insertion in his midsection and, seven times a day, he attaches a funnel-like attachment to the end of the tube and pours the contents of a small nutrient-rich shake into the funnel and watches as it slowly disappears into his torso. He takes in water this way, too.

“So,” I asked, watching as he poured the last of his lunch into his tube, “has it been a good career, overall, pawnbroking?”

“I’ve been happy with it,” said Hook.

I told him that I imagined pawnbrokers were pretty grounded people and that they probably didn’t go in for much philosophizing. “But,” I said, “do you remember how you felt a few weeks ago when they told you the cancer had come back?”

Hook wore a mint-green fishing shirt the day we spoke. His eyes, nearly the same faded blue-green as his shirt, pooled at the memory.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “It can’t have been easy.”

He shook his head.

“No?” I asked.

“There are,” Hook said — he gestured widely with both arms and then suddenly let them drop to his sides; he continued, softly — “there are no words for it.”

“No words for it?”

He nodded.

I’d run out of questions. Hook reached for his pen and began to scribble. “IT MAKES YOU LOOK AT LIFE DIFFERENTLY.” He looked up at me, waiting. I read his words aloud and nodded. He went back to the pad. “IT MAKES YOU LOOK AT LIFE A BIT DIFFERENTLY I TOOK CARE OF ALL REGRETS I HAD THAT BOTHERED ME MOST MAINLY OLD FRIENDSHIPS.”

“Was that a good thing, in the end?” I asked, inanely.

He smiled. “I think so.”

“That’s a meaningful lesson I could apply to my own life,” I said, and meant it.

Hook spoke slowly and with labor. “If you don’t,” he said, “in your last minute of life [inaudible].”

I didn’t understand him. “I didn’t catch all of that,” I told him.

He repeated himself. “In your last minute of life?”

“Yes,” I said.

“It will haunt you.” He pressed down hard with his pen. “IT WILL HAUNT YOU.”

TOWARD THE end of our visit, an elderly woman entered the store with two small valuables. “I want to know if you can give me some cash on these two,” she said. “My daughter’s house burned down in Texas and I need to send her a little money.”

“How much?” Hook asked. The woman was silent. Hook pointed to his notepad: “HOW MUCH?” He then gestured toward his mouth and said, “I’m sorry, I lost my tongue to cancer.”

The two negotiated a price and it was agreed that Hook would give her cash for the items, but then hold them for a period in the event that she wanted to buy them back. A sort of layaway arrangement.

“OK,” the woman said, “can I pick them up in a month?”

“Mm-hm,” Hook said.

“That would be a big help,” she said, “a big help. I just had a friend that had cancer.”

“That’s what I had,” said Hook.

“This kid, he ran with my own kids,” she said. “He was only 49.”

“This is what I have to do,” said Hook, pointing to the water bottle and empty drink carton on the table.

“That’s your lunch?” The woman asked. Hook nodded. “Well, good,” she said.

Hook counted out two even stacks of cash. “Yes, this will be helpful,” the woman said, scooping the bills up from the table. “I can at least give her an extra hundred this way. Thank you, thank you. What’s your name?”

Hook spoke carefully. “Mike,” he said.

“Matt?” the woman said.

“Mike. M-I-K-E.”

“Mike. I’m Donna. Thank you, Mike. I’ll see you in a month. This will at least give her — see, her birthday was yesterday and her house burned down. Happy Birthday, Cindy, huh? See you in a month, Mike.” The woman turned to leave, but when she got to the door, she called back toward the shopkeeper. “Mike?”

“Yes,” said Hook.

“Boy, Mike, you’ve sure got a lot of stuff in here.”