by RICK DANLEY // March 10, 2018

You’re in the cockpit of a B-1 bomber. It’s the middle of the night. You’re somewhere over northern New Mexico, slicing through the black sky at about 600 knots. There are four of you in the plane. The copilot to your right, his face made ghoulish by the green glow of the instrument panel. Seated behind you — you can see them if you strain — are your two weapons systems officers. Outside the aircraft is all engine noise and rushing air.

And then it happens: the plane begins to fall from the sky.

You check your altimeter: 15,000 feet. You’re losing altitude. 10,000 now. 9,000. 8,000. The plane is no longer under your control. 3,000 feet, now 2,000. The ground closing in. You’re at 1,000 feet. And then, at precisely 500 feet above the desert floor, the 400,000 pound metal casket that is towing you earthward ceases its descent, landing like a feather on an invisible cushion of air.

But the ride isn’t over. At this point, the bomber — the “Bone,” as its nickname runs — races forward, hugging the ground at a determined 500 feet. Now, here you are, traveling again at 600 mph, still enclosed by darkness. The plane seems to be flying itself. You can’t see five feet in front of the windshield. You peer down at your display radar; there’s elevation ahead, a mountain range, and you’re heading straight for the rock face. Just before impact, however, the machine, on its own, lifts swiftly up and over the cliffs and then resumes its parallel journey along the earth’s surface — back at 500 feet — maintaining its same poised distance from the ground, as steady as a sea bird over open water.

But none of this is a surprise to you. It’s all been according to plan. Just before your hasty descent from 15,000 feet you had enabled the B-1’s terrain following system, an aerospace technology that sends radar waves down into the ground in front of the plane; a system which, when combined with the plane’s autopilot function, allows the bomber to sustain a fixed altitude above ground level. The technology was originally created as a way to breach enemy territory beneath the level of radar detection.

“With this system, you’re turning the aircraft but you’re not controlling the up-and-down. The plane itself is controlling that,” explained Tyler Ringwald, a graduate of Iola High School, a former flight instructor, and, at 29 years old, an active B-1 bomber pilot in the United States Air Force. “If anything goes wrong, the plane is auto-cued to go up and away from the ground. The computer does that for you. If it senses any weird glitch or any other danger, it instantly climbs you away from the ground. Obviously the biggest threat in this business is the ground. It wouldn’t take you a second to just….” Tyler makes a downward gliding motion with his hand. “It definitely requires a lot of trust in the technology.”

WHILE THE aeronautical technology in a plane like the Rockwell B-1 Lancer is of brain-bending sophistication, its very existence depends on the humble but no less ingenious tinkering of two bachelor brothers a century prior. To celebrate this history of air travel, the Iola Reads committee — in conjunction with their winter book selection, David McCullough’s “The Wright Brothers” — have funneled months of planning into Iola’s first-ever aeronautics fair. The fair, held at Riverside Park on Tuesday, runs from 1 to 7 p.m., and is open to plane spotters of all ages.

WITH ITS WIDE skies and crop-tiled terrain, the vast prairie sea of Kansas has long been a favorite setting for avid aeronauts — flyover country in the very best sense — and this has included southeast Kansas, too.

For instance, in October of 1911, the Viz Fin Flyer, the first aircraft to fly coast-to-coast across the United States, made an unexpected pit stop in Moran. Rural telephones notified farmers from miles around that the flying machine was circling overhead. A large crowd gathered to see the fabled pilot, Calbraith Perry Rodgers, put his biplane down in Alfred Johnson’s cow pasture. A train following the Vin Fiz Flyer pulled into the station just after Rodgers landed, at which point the aviator’s wife, Mabel, rushed toward the plane with two sandwiches and a quart of milk, which the large aviator swallowed in a hurry. Rodgers stretched his limbs one last time and was gone. But for as long as the first-ever transcontinental flight is remembered, Moran will be a significant bullet point in its story.

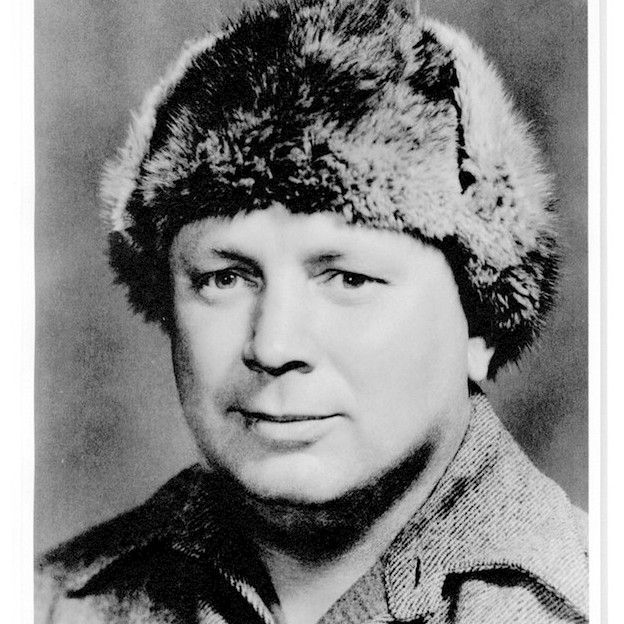

The Iola Register recorded, too, the early doings of Colony-native Merle “Mudhole” Smith, who, in the middle part of last century, ascended the ranks from bush pilot to president of an Alaska airline, with stints as a wartime rescue pilot and circus barnstormer in between.

In 1976, in fact, Mudhole Smith was named to the Aviation Pioneers Hall of Fame, where his plaque hangs alongside those bestowed upon the brightest lights in aviation history — the Wright brothers, Lindberg, Rodgers, Clyde Cessna, William Piper, Amelia Earhart.

But Mudhole’s ascent wasn’t without the usual turbulence that accompanies the overeager strivings of ambitious young people. The Register, at the time, recorded a conversation with one Iolan, Mrs. Flora Farris, who recalled meeting Mudhole in 1935.

As a Colony High School teacher and junior-class sponsor, Farris had taken her class to the Colony fair where Mudhole was selling rides on his Stearman biplane. One of the junior girls begged to go, but couldn’t without Mrs. Farris as escort. After much pleading the teacher reluctantly agreed to go. As she tells the story:

“It was too short a pasture, really, to take off in. There was this one little tree out in the middle, and we couldn’t tell, of course, with the wind whistling in our ears, but he couldn’t get the plane going fast enough to get over it.

“So just as he got to the tree, he tried to tip one wing up to go over it, and the other wing caught the ground. We flipped over into a ditch and broke my arm.

“That was really my only contact with him,” she added. “But it was enough.”

IF NONE achieved Mudhole’s level of fame, the list of successful area aviators continued apace.

To recall only the most recent examples, the Register marked that crystal-blue day in April of 2010 when then Humboldt High School sophomore Miranda Meyer became the youngest pilot to take off and land solo at the Allen County Airport.

A year later, 62-year-old Elvin Nelson fulfilled his own lifelong dream by building for himself a two-passenger airplane — from scratch. The job took a year and a half to complete. Asked how he did it, the Iolan responded: “I just used the instruction manual.”

Then there was the couple, Barry and Jennifer Lamb, who commuted to their jobs in Olathe in a 1966 Cessna 150, which they’d launch from a half-mile grass strip next their home in rural Mildred.

Fast forward to the summer of 2013 when a 1929 four-seat monoplane with a 44-foot wingspan was disinterred from the loft of the old Iola Planing Mill where it had laid moldering for more than 80 years.

And then there was poor Kenneth Weaver, who gave new polish to the phrase “high flyer,” when he landed his small passenger jet at the Allen County Airport with a modest 200 pounds of medical-grade marijuana stowed on board. Local law enforcement soon relieved Weaver of his burden — as well as his plane — and the criminal courier was sentenced to a year in federal prison. In addition to his prison sentence, Weaver forfeited to the government more than $450,000 in cash, a 2007 Bentley Continental, and a 2010 BMW X.

Now, with a name like Wright, you can’t go wrong. Last year, the Register profiled Chanute resident, David Wright, who owns more than 15 high-end remote control airplanes, which every so often darken the skies of northern Neosho and southern Allen counties. Some of his models, explained Wright, are as expensive as $1,500.

Finally, there was this crash course in flying…. It took Rob Jordan, a flight instructor at Allen County Airport’s erstwhile Accel Aviation, more than 20 years of piloting before he experienced first-hand a case of traumatic engine failure. But on a bright spring morning in 2010, Jordan was giving a lesson to a man named Ray Smith when the plane’s engine cut out and Jordan was forced to execute an emergency landing. The front landing gear of his Kitfox light aircraft snapped off and the aircraft skidded to a halt in the pasture directly in front of the rural home of Bill and Charlotte Owens. Charlotte, who would pass away in 2015, went out to check on the men. “They didn’t seem to be too shaken up,” she told the newspaper at the time. “They may have been a little excited. They sure were talking fast.”

IOLA IS THE hometown, too, of Amy Lewis, who numbers among the Air Force’s select minority of female F-16 fighter pilots.

A 1997 graduate of Iola High School, Lewis — formerly Ringwald — was a freshman at IHS when a cadet from the Air Force Academy paid a recruiting visit to the school. The prospect of flight excited Lewis’s interest and, by her junior year, she was already fashioning plans to attend the academy in Colorado Springs.

There are a number of career tracks within the ranks of the Air Force that an academy graduate can pursue. But, for Lewis, flying fighter jets was the only goal. “For some reason,” she remembered, “I always just felt I could do it.”

And the Air Force agreed. Lewis did well at the academy; she excelled in pilot’s school; and, not long after, she was among a preferred group chosen to fly the F-16, at that time one of the Air Force’s most advanced fighter aircrafts.

“To me,” said Lewis, who remained throughout her years of active duty the only female F-16 pilot in her squadron, “it’s just a thrill ride to fly fast jets. I remember the first flight in the T-38, which is a fighter-trainer — you throw the throttles and the afterburner, and you just feel yourself being pushed against the seat with all that thrust. And it’s even more in the F-16. I mean, why wouldn’t anybody want to do it?”

This mother of two, who, in 2006, flew 56 combat missions over Iraq, and who is currently a flight instructor at the Air Force Academy, is also the older sister of B-1 bomber pilot, Tyler Ringwald.

Tyler, currently a captain in the Air Force, recalled Amy’s influence on his choice to pursue a life in the air. “I think, growing up, a lot of people wish they had a superpower. For me, it was flying. I’ve always wanted to do it, always, ever since I was little. But the fact that my sister flew was important. It made it seem possible.”

WHILE RENOWNED in the early part of his career for his daredevil flying and in the latter part of his career for founding a company that would go on to form part of Alaska Airlines, the proudest moments in the life of Mudhole Smith were the 100-plus mercy and rescue flights he conducted during the Second World War.

And it’s into this lineage of flight that Allen County Commissioner Jerry Daniels fits.

Daniels, the owner of Humboldt Helicopters — which offers flight training as well as charter tours — has been, in his time, a helicopter crewman in the National Guard, a dual-rated pilot for the Kansas Highway Patrol, and a longtime lead helicopter pilot for Med-Trans, an air medical transport service based in Chanute. In his 26 years of flying, the Humboldt native has logged more than 3,000 hours of flight time.

But his keenest memories are those flown in the spirit of public service. One mission, in particular, stands out.

Daniels’s medical helicopter was one of the first to land in Joplin in the hours after the deadly 2011 tornado. The storm had knocked out power to most of Jasper County, and Joplin was completely dark as the pilot descended on the city. It was eerie, remembers Daniels. The medical helicopter landed at the city’s only remaining hospital. The emergency room was pure chaos. “There were patients everywhere. It was almost overwhelming as far as triage goes. We just grabbed the first injured person we came to, and started flying patients out.”

Daniels and his crew did this all night. Coming and going from Joplin to Kansas City, Joplin to Wichita. “You know, when the sun came up and we were heading back to Chanute,” recalled Daniels, “you were tired and you were worn out, but you reflected on what you saw. All these innocent people, bombarded by this huge storm, their lives wiped away. It was hard, but, for me, it was satisfying to be a part of it, and I was glad that I could offer some small amount of help. I still think about it.”

AND YET when asked to pluck their favorite moments from their respective flying biographies, all three pilots — Daniels and the two Ringwald sibs — point to moments when they’ve been able to pass along their knowledge of the air to a younger pilot. All three are or have been flight instructors.

“As an instructor in the T-38,” said Amy Lewis, “my favorite thing was taking a student up on his [or] her first solo formation flight. I would be solo in my own aircraft, and my student would be solo in his [or] hers. I would lead that student through a formation sortie where [they] would be as close as three feet from my wing at times and flying at speeds up to 400 knots. After landing, seeing the excitement in [their] face and the boost in confidence that followed was very special to me.”

But then sometimes the joy is just the simple disobedient joy of slighting gravity. “Every once in awhile,” said Tyler Ringwald, “when you’re just cruising and you see a sunset or something else in the sky, you do try to take a few seconds and think, ‘This is awesome.’ These planes are so complex, you know. It really is a miracle. I mean, think about it: we can fly.”

This article originally appeared in The Iola Register on March 10, 2018. *