by RICK DANLEY // October 21, 2017

It’s not a coincidence that Milton gave the devil the best lines in “Paradise Lost” or that of the three books in Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” the “Inferno” is the only one anyone still bothers to learn. Or that set next to the regal menace of a character like Darth Vader, Han Solo appears as dull as the kid on the side of a can of Dutch Boy Paint.

Just as it’s no wonder that the most passionate traffic this newspaper’s Facebook page ever receives is in the aftermath of a murder or in the wake of some other baleful crime.

Villainy is sexy. Vice is appealing. “The forces of good are necessarily lacking in vitality,” observed the critic Clive James, who was himself writing about the author of “Paradise Lost.” “[Milton],” said James, “faces the insuperable problem that nice angels are not interesting.”

In other words, the baddie is always more compelling than the boy scout.

Speaking before a meeting of the Allen County Historical Society, Larry Manes — who years ago appealed to the higher minds of this community in a speech he dedicated to the early-day heroes of Allen County — on Thursday gave his audience what they really craved: five tales centered on the county’s early-day “villains.”

One would have to ring up Manes himself, who is an elegant and intelligent speaker on most any matter, to get the full rundown on all five of his subjects — Alexander Driscoll (stabbed a man; executed), John Bell (raped a woman; hanged), Elzy Dolson (killed a boy; lynched), Charley Melvin (blew up a few pubs; imprisoned). For now, though, here’s a peek at one such story. We’ll call it, for the purpose of this article…

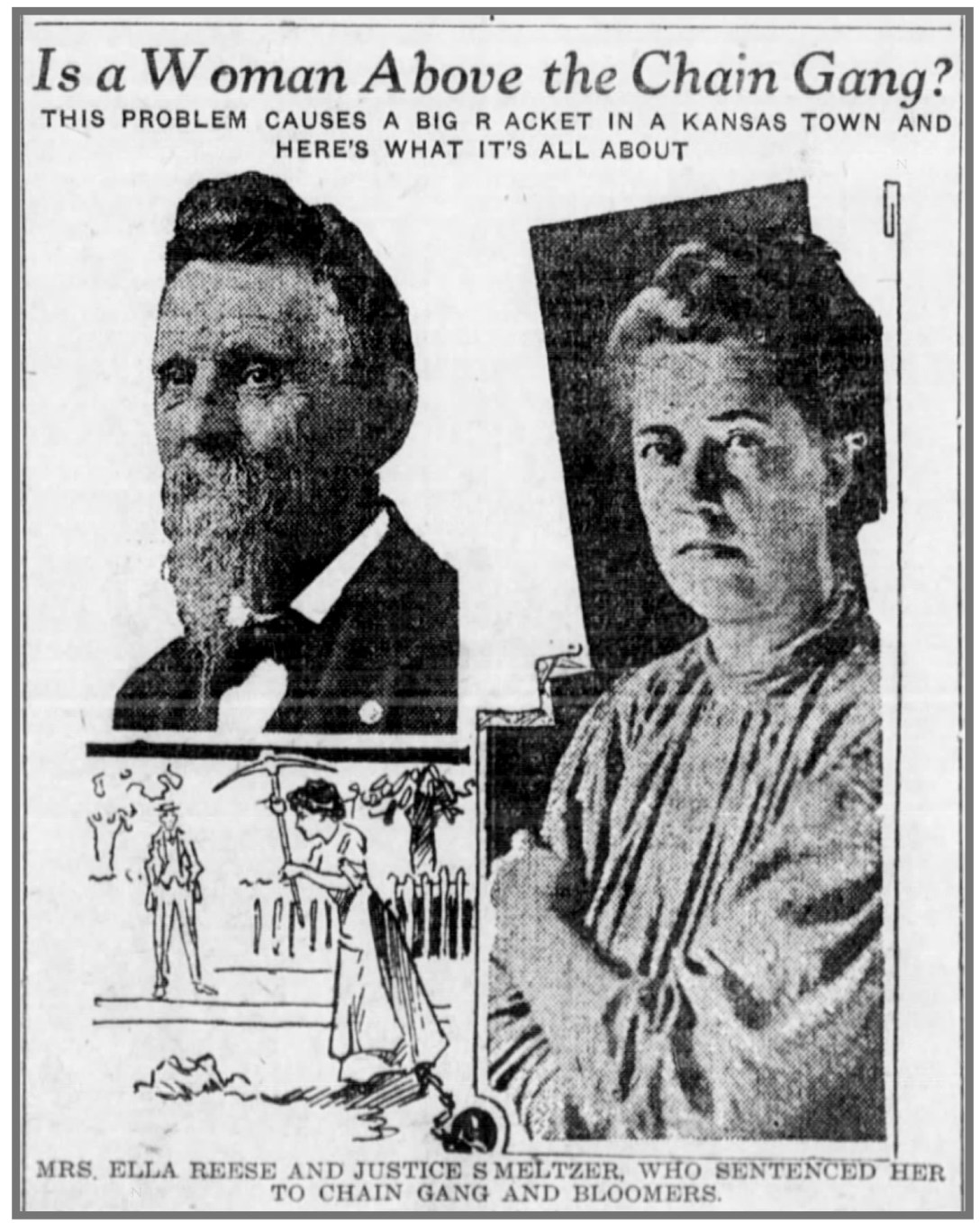

“The Case of Ella Reese”: Or — as an East Coast paper labeled it at the time — “The Sex Problem in a Kansas Town”

In the late summer of 1911, Municipal Judge D.B.D. Smeltzer sentenced 35-year-old Mrs. Ella Reese to thirty days of jail time and hard labor on the charge of “immoral conduct.” Reese was accused of, and eventually confessed to, operating “an institution of ill-earned wages,” as this newspaper termed it—“a disorderly house in which she was the sole inmate, and in which men and minors gathered o’ nights in the outskirts of the city.”

It wasn’t a fancy place, Ella Reese’s. There was no music or dancing, no bright lights. The mood was strictly transactional. Another journal of the day accused Reese’s home of having “the same, drab, passionless, dull color” as its proprietress.

But Reese gained a healthy reputation among the more amorous laborers of the day, who poured into Allen County from hither and yon to work in the smelters during the waning years of the gas boom. And she apparently operated at a profit for most of her years in business. But, like many bottom-line tycoons before her and after, she was a victim of her own ambition.

See, the infraction that finally plunged Ella Reese into hot water — which is to say, the outrage that finally brought her to Smeltzer’s attention — was her decision to open her doors (so to speak) to a teenage clientele.

“It was for the sake of the welfare of the boys of Iola that I decreed that Mrs. Ella Reese should go to the rock pile,” declared Judge Smeltzer, who chose not to exempt Reese on account of her gender from the same hard labor that was his usual prescription for men.

Smeltzer, with his thick gray mustache and long pointed beard, was described in various contemporary reports as a strict man, upright by reputation, a 30-year citizen of Iola, “aged, honest as a ten-penny nail,” “a stern, radical churchman,” “a Presbyterian,” “a Calvinist,” a “Christian gentleman.” He wrote a letter to the Register in the days following the trial in which you can almost feel his pen trembling with moral upset. In it he condemns again a scenario in which “beardless boys were lured perhaps willingly into the abiding place of the accused.” (The phrase “perhaps willingly” is a poignant inclusion on the judge’s part; the only signal throughout this whole ordeal that the desiccated old jurist retained at least a sense memory of the human juices that motivate the great majority of teenage boys.)

But, with a few stark exceptions, villainy is a conditional, historically contingent category, not an inherent one. A villain in one period — Oliver Cromwell, say, or John Brown — can be dubbed a hero in the next.

Manes’s talk places the black hat squarely on the head of Ella Reese — which is a fair enough perch — but many citizens at the time were sure that Judge Smeltzer’s crown held the better fit.

Poor Smeltzer, unwitting Smeltzer — our upright Christian gentleman had hardly rendered his verdict before the residents of Iola took against him. “How dare he consign a woman to the same physical labor as a man?” they asked. The town was incensed.

“The insurrection in Mexico wouldn’t be a shadow compared with the one I’ll start if Judge Smeltzer attempts to work Mrs. Reese on the chain gang,” bawled Guilford C. Glynn, Iola’s street commissioner. “I’m not defending the woman of the charge made against her, but I’m resenting the punishment proposed. A woman in bloomers working on the streets of Iola! Is it possible to conceive of such a thing? It isn’t for me and so long as I have charge of the street department Judge Smeltzer may order this woman to the chain gang till he’s unable to speak and I’ll never budge. She can’t work on the streets. I won’t permit it.”

The same article quotes Iola Mayor C.O. Bollinger on the matter: “‘[She] might wash the windows or scrub the floors of the city hall. That wouldn’t be so bad. But we couldn’t under any circumstances countenance working a woman on our streets, and in bloomers; why, it’s absolutely shocking.”

The chief of police became particularly overheated at the thought of subjecting the public to an eyeful of this special undergarment. In fact, he contested, “I believe the law gives me power to take the woman into custody if she arrays herself in those harem-scarem things and appears in public.”

Smeltzer, who probably expected plaudits for his condemnation of a local lady of the night, must have been shocked by the backlash, which began in Iola and within hours — thanks to the Associated Press — had spread nationwide. But Smeltzer was nothing if not a man of principle. He never budged. “The law is plain. It says city prisoners must work. Road making is the only work we have for them, so I found Ella Reese guilty…and sentenced her to the chain gang. She will have to serve. The law makes no sex distinction.”

The masses, though, were unmoved and the judge quickly became an object of scorn.

“I am the most abused man in Kansas,” Smeltzer told a crowd in Cherryvale. “And it is all because I did what I conceived to be my duty in administering punishment to a vicious woman whom the evidence showed was guilty of attempting to break up a home.”

He went on, elsewhere, a little richly perhaps, to compare himself to Henry Clay, whose famous claim “I would rather be right than President” led the furry-faced old judge to avow that he, too, would “rather be right than to gain any office in the gift of the people by dishonesty. … I am not appealing for notoriety, nor for sympathy, but for justice.”

There was a famed suffragette of the day by the name of Elizabeth Barr. Her response to the judge’s cries of self-pity? Big whoop.

Barr was a nationally prominent activist and respected magazine editor, who, like the Iola commissioners, believed it beyond the pale of an advanced society that a woman should be sent into the streets to work alongside men. “Occasionally in the process of civilization there appears a specimen of a former order of being in the midst of a highly developed race with which this representative of pre-historic times has little in common,” wrote Barr. “Such a freak is Judge Smeltzer of Iola.”

Perhaps fearing that her point would get lost in the nuance, Barr continued: “He belongs to the donkey age, having all the characteristics necessary except the ears, and I would like to be one of a volunteer crowd of women to go down to Iola and attach the missing appendages of his anatomy, put a halter on him and lead him about the streets.”

Barr continued in this vein, even offering to store “the critter” in his own stall.

“Because he thought it in his power to do so, he determined to force a woman prisoner to work at labor too hard for any woman, and on the public streets, in a chain gang with the men.”

Women, who at this point in history had been advocating for the vote for more than sixty years, were still almost a full decade away from total suffrage, a point Barr acknowledged in the Reese case. “Of course the question is put, if women are to vote on equal terms with men, should they not suffer the same punishments for crime?”

Her answer: “Certainly, they should…. A woman can suffer the same punishment for crime scrubbing, cooking or sewing that a man can working on the streets. But if a woman is made to work on the streets she suffers a greater punishment than the men because she is not physically able, as a man is, to do such work.”

The anti-suffragist press rounded fiercely on Barr and her allies, endeavoring with no shortage of snark to expose what they deemed the hypocrisy in her line of assault.

A newspaper in Chicago, for one, accused this particular group of suffragettes of having abandoned their “sincere regard for logic.” For “what more signal triumph of their cardinal principle—the equality of men and women—could they possibly demand than the condemnation of Mrs. Ella Reese to labor on the rock pile in full equality with all the male prisoners engaged in the same occupation?”

“And yet,” this writer continued, “when a Kansas judge, no doubt with the idea that he was about to make himself popular with the suffragette contingent, proceeds to apply their principles in practice and to admit Mrs. Reese to the freedom of the masculine rock pile, there rises a chorus of denunciation, from Iola to Topeka!

“The only conclusion from this affair…is that the suffragettes want all the equality with males that they conceive to be agreeable, but are opposed to the surrender of any particular privileges that they find rather convenient.

“In brief, the suffragette ladies seem to want the vote and the alimony, the ballot and the seat in the car, the suffrage and the deference to which the sex has so long been accustomed, the pleasant but not the disagreeable, the selecter and more savory portions of the hog, but not the whole animal.”

And so it was that for a few muggy days in the late-summer of 1911, Iola became in its modest, morally complicated way a center for questions of civil rights and a living reminder of the fractious, complex, ever-shifting definition of a word as often uttered as “equality.”

IN THE END, bowing to consensus, Mayor Bollinger upset the decree of Judge Smeltzer and issued a pardon to Ella Reese. And, on the afternoon of Aug. 11, after less than a week in confinement, Mrs. Reese “stepped from the city jail into the arms of her husband, Garfield Reese.”

“I’ll not turn her away now,” Garfield Reese told this paper. “We can go away from here and live. Everything will be all right and we will be happy again.” Mrs. Reese took up her 3-year-old son and the family descended the sidewalk, leaving Iola, and receding forever from the public record.

D.B.D. Smeltzer, on the other hand, served many more years as judge in Iola. Smeltzer grew up in a slave-holding home in rural Maryland but made the decision as a young man to fight for the cause of the Union. He moved to Allen County soon after the Civil War and took up the practice of law. In his late age he was known to rail against speeding cars on the town square and to hand out tickets to boys who rode their bicycles on the sidewalks. Even into his 70s, growing impatient while waiting for his morning train, the old judge would sometimes take off his coat and walk from Humboldt to Iola or from Moran to LaHarpe or from Piqua to Iola. In his very last years, Judge Smeltzer would make large bouquets from the flowers he’d collected from the trumpet vine that grew near his house. He would deliver the arrangement to a favorite friend or to the front office of a local business. It was said that the judge would wave at any man, woman or child he passed on the street, no matter their station. He was a man who doted on his daughter and on his wife, who preceded him in death by several decades. The judge himself died in the summer of 1936. He was 95.

This article originally appeared in The Iola Register on October 21, 2017. *