by RICK DANLEY // November 25, 2017

NEOSHO FALLS — On April 18, 1945, 18-year-old Wesley Carroll stood with the other recruits in line for the 120-foot high dive at the Great Lakes Naval Station in northern Illinois. As he neared the ladder, a man from the master-at-arms’ office approached. He pulled Carroll out of line and told him he was needed at once in the main office.

Carroll gathered his things and followed. As they crossed the drill field, Carroll asked the officer, “Well, what the hell kind of trouble am I in?”

“You’re not in any trouble,” the man said. “Your dad got killed.”

EARLIER THAT DAY, around 7 a.m., Gene Carroll was out milking cows. The Carrolls — mom, dad and nine children — had a few acres on the edge of Kansas City, Kan. Gene’s mother was in the house fixing breakfast. The children were getting ready for school. Gene’s father had gone out to the garage to finish welding a plow.

Gene was 13 at the time, and was nearing the end of his morning chores when he heard the blast. Gene’s mother raced out to see what had happened. The other children followed. The entire garage was sheathed in fire. His mother shouted for Gene to shoo the cows from the barn, which he did. The children called out for their father, but there was no answer. The fire traveled quickly, eventually reaching the cow barn. The telephone lines were down that day, and so the fire department was slow to be notified. The children, with their mother, searched everywhere for Mr. Carroll, but to no effect. The acetylene tank he’d been holding had exploded in his arms. He was killed instantly.

“They finally found him,” remembered Gene. “But it wasn’t good.”

“They told me he was blown up into the hayloft,” said Wes. “And a guy down the road, he says the blast shook him clear away from his breakfast table.”

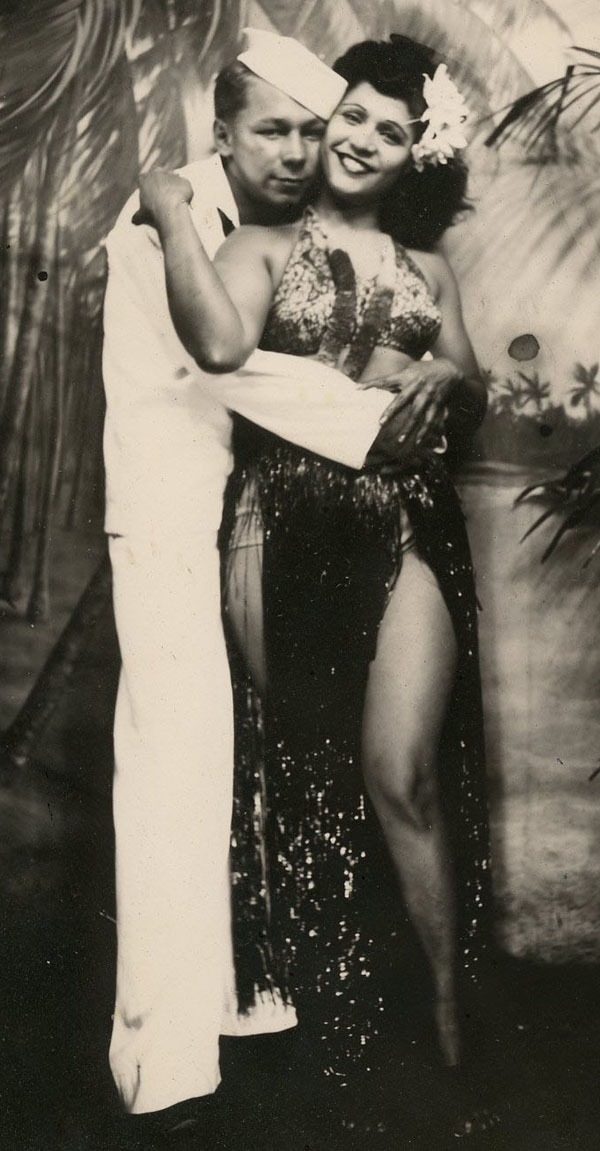

WES BORROWED thirty dollars from the Red Cross to take a train back to Kansas City for the funeral. But the war was still boiling in Europe and the Navy needed him. In a few days, he was back at boot camp, and soon after that he shipped out to Pearl Harbor, where he remained through the end of the war.

Asked to recall that day in August when the last of the Axis powers surrendered, the 90-year-old offered this account: “Well, I’ll tell you, we had to give 45 dollars for a fifth of Paul Jones whiskey. Oh, hell yes. That was your black market over there. That’s what you had to pay for stateside whiskey. Oh, you could get kanaki juice and beer, stuff like that. But, anyway, we were at the outdoor movie that day, 15th of August, 1945. All of a sudden, all the lights on the base come on — search lights, street lamps, every damn light. And over the loud speaker, we heard: ‘THE WAR HAS ENDED.’ We got crocked. We had about four cases of beer, two gallons of kanaki juice and we had that fifth of Paul Jones. I tell you, that night that whole damned island lit up.”

THEY DON’T make them like Wesley Carroll anymore, and that’s too bad. But it should be said that Wes, who attempts through a great deal of indirection and joking, to conceal his inherent gentleness, also has the grand habit of cussing like it’s going out of style. This, then, may be the place to warn gentler readers of the mild four-letter oaths that lie ahead. To remove these words entirely from his way of speaking here would be like plucking every piece of candy from a fruitcake — you could do it but you’d lose all the flavor. The more scabrous words, I’ve struck from the article or else replaced with brackets. The nicer ones, though, I’ve kept.

IT BECAME immediately clear, after the accident that killed the elder Carroll, that the family would require a new provider. In December 1945, Wes left Pearl Harbor for Seattle, where he was discharged, given dispensation from the Navy so that he could return home to take care of his family. The next day he boarded a train bound for Kansas City.

The train made frequent stops, including one in a little town in Wyoming. Wes had a few minutes to kill. There was a beer joint across from the station that had his name on it. Inside the dim saloon, Wes spotted a slot machine in the corner. “I had one silver dollar on me, to buy a pop. Well, I stuck it in the goddamned silver dollar machine and hit it for 16 silver dollars. Hell, I still had my blues on — so no pockets. I had to carry the rest on the train.”

Wes arrived home on Christmas Eve. Coming down the street, he could see, as he neared the house, his younger siblings gathered at the end of the driveway. He hadn’t seen them since their father’s funeral. The next day, for Christmas, he gave each a silver dollar. “And there was one from 1900, and that’s the one I give mom, because that’s the year she was born. Her and dad both.”

WES WAS ALWAYS going to be a machinist. His talent bent in that direction early. His dad was a machinist, and after serving his apprenticeship, Wes eventually landed a job as a machinist, too, at Colgate-Palmolive, in the Kansas City plant.

Every paycheck Wes collected at Colgate went toward the family. He and the next eldest brother, Dave, assumed many of the other burdens of parenthood, too.

Wes and Gene both recall an afternoon when the younger Gene, then a bumptious high schooler, lobbed some defiant comment toward their mother.

“He sassed mom,” remembered Wes, “and so I had to kick his ass. I had to. I had to do it. But, see, I was little and he was in good shape. I threw him on his ass real fast and got astraddle of him. I says, ‘One of these days, you are going to be in some dirty foxhole and you’re going to think about mom and be sorry you ever said that.’”

Late last week, Gene and Wes sat across from each other in the small back room of Gene’s double-wide trailer, which sits at the corner of two dirt roads in Neosho Falls. Wes lives in the trailer across the street.

“And I was,” recalled Gene, who will be 86 in January. “I was in one of those dirty foxholes.”

“When he come back,” said Wes, “that’s the first damn thing he told me. He says, ‘Wes, I was there.’”

ONE EVENING in late 2014, Gene walked into the living room and told Jenny, his wife of 60 years, “I think I’m having a stroke.” That’s the last thing he remembers before collapsing into a seizure.

Jenny called an ambulance. Then she called Wes, who came straight over.

Gene was flown by helicopter to KU Medical Center in Kansas City. A blood vessel in his brain had ruptured. After landing, he was rushed into intensive care.

Once stabilized, he was taken to his hospital room, where he would spend the remainder of his recovery. The room was across from the hospital’s helicopter pad.

“Helicopters would come in and leave,” remembered Gene. “I’d hear them coming and going. I sat there, listening. My son-in-law was there and I heard him say, ‘Everybody just shut up, he’s remembering Korea.’ I heard him say that. That sound — it brought it all back. See, I forgot about Korea. I raised five kids. I knew I was a vet, I knew I was over there, but, hell, that was it. But, starting then, I remembered everything that happened to me when I was in Korea. I went to a psychiatrist up there and he said it was post-traumatic stress syndrome. They said it all comes back. And it did.”

GENE remembered his very first time on the frontlines. His platoon was on its way to taking Hill 812. He passed by a corpsman who was doing everything to save a young man whose eyes were still open but whose whole side had been shot out. He remembered the tall mountain north of the 38th Parallel. The North Koreans would roll cannons out from tunnels carved into the top of the mountain and rain fire down on the Americans. U.S. troops positioned downhill never succeeded in firing back. One day, Gene and his unit looked out toward the mists lying thickly over the Yellow Sea and saw, in the bay, an American battleship moving toward the shore. The men watched as the ship raised its missile turrets and opened fire on the mountain. The fusillade touched off the Korean armaments in the tunnels and when Gene turned back around it was to see the entire top of the mountain explode in a ball of fire. The Marines cheered. He remembered, too, walking in the same frigid uplands and looking up and seeing a rainbow in the sky at midnight. He remembered the time a sniper kicked up dirt in front of him, remembers diving into the nearest trench. When it was quiet again, Gene grabbed his 3.5 bazooka. He was a member of the Marine Corps weapons company. He located the bunker from which the sniper fire hailed and he “blew the damn thing apart.” He remembered an officer early on telling him, “You’re scared the first time you go on the frontlines, because you don’t know what will happen. The next time you go on the frontlines, you’re scared because you do.”

BUT GENE DOESN’T need the gossamer threads of memory to connect him with one of his most harrowing combat moments, the results of which are written on his body even today.

It took place on Hill 884. They were short on the frontlines, so Gene’s unit moved up to fill the gaps. “It was around the 20th of December, high up in the mountains. It was cold as billy hell,” recalled Gene. “So, anyway, they said dig in. So I dug a little foxhole and put my shelter-half over it. This other kid, on the other side, he did the same thing. I woke up the next morning and I had my foxhole clear full of water. The tarp was down on my face. Hell, we had about two feet of snow that night, and that water got in there. So, anyway, the sergeant came down and says, ‘Oh, I forgot about you guys down here.’ And I says, ‘I need a corpsman.’ He says, ‘OK.’ So he yells up for a corpsman. The corpsman came down and I pulled up my pant legs and I says, ‘What’s wrong with me?’ I had little puss-y blisters all over my legs. He says, ‘You’ve got frostbite.’”Today, the fifth-born Carroll walks with a cane on account of the intense pain and neuropathy in his legs and feet, a legacy of those cold-weather injuries.

“DID YOU WORRY about Gene while he was in Korea?” I asked Wes.

“Worry? Worry?” said Wes. “What the hell would I worry for?”

And it’s true, Wes had his hands full back in Kansas City. In 1952, while Gene was charging up one frozen alp or another, Wes was moving the family out to a new patch of land on 53rd Street. There, he built a large, gambrel-roof barn with a two-room loft-style apartment at the top. “I built it for mom,” said Wes. “And the room above was so that she could rent it out and always have an income coming in.”

Soon after that, in his thirtieth year, Wes was married. “This one was my first wife,” he explained. But the two lovebirds bickered from the jump — “Actually, she was a no-good [ed: a woman known for her vast promiscuity] and that’s all there is to it.” It wasn’t long before Wes grew weary of married life. One night, the couple had a bust-up that sent the spurned groom hurtling down a dark highway toward — “now, what’s the name of that damn town in Arkansas? Paragould! Paragould, Arkansas.”

He knew a couple who lived down there. He’d met them in a trailer park the year before. The man was a high-voltage lineman. The wife’s name was Faustina. Wes would cool his heels at their place for a few days.

One day, he approached Faustina and asked where her husband had gone. She told Wes he’d gone to Hot Springs to the horse races. “Well, let’s get on over there,” said Wes.

Faustina put her foot down. “I don’t gamble.”

Wes recalled his conversation with the woman across a distance of 60 years: “‘What do you mean you don’t gamble?!’ I asked her. ‘You gamble every day.’ ‘I don’t either,’ she said. I says, ‘You gamble every day to live, don’t you?’ I said, ‘You got cows out there.’ I says, ‘You gamble on them that they’re going to live long enough to make market, so you can get money out of them. You’ve got all your crops out there. You gamble on them.’ ‘I never thought about that,’ she says. ‘Well, I said, then you gamble, don’t you? You might not go to gambling houses and gamble but,’ I says, ‘you gamble. Everybody gambles. You gamble on life.’”

The two hit the road for Hot Springs that morning.

After a week in Arkansas, Wes returned to Kansas City. It turned out, however, that he had the kind of job where you couldn’t just disappear for 10 days, unannounced, on a gambling binge, and expect to resume your 9-to-5. Wes was fired on the spot.

OVER THE NEXT few years, Wes travelled across the southern United States, working a variety of jobs — at a shipyard in Galveston; on an offshore drilling rig in the Gulf; making crew boats in Sulphur, Louisiana; then hauling top soil for rice farmers in that same sweaty town. “Then I met this guy, Burl, a mechanic, and he wanted to go up to Norman, Oklahoma. He had a relation up there. So I said, ‘OK, I’m ready to go back to Kansas City anyway.’ I bought an old…an old — now, what the hell car did I get then?”

For anybody else, this would be an idle question. Not so with Wes.

WES CARROLL is the kind of guy who scratches his head when asked to recall the names of some of the women he’s loved through the years, but he’s never forgotten the make and model of any car he’s ever owned. Over the course of a single two-hour conversation last week, these are the cars Wes name-checked.

1940 Chevrolet Sedan — One of the cars destroyed in the blast that killed his dad.

1933 Ford — “Flattened” in the same blast.

1956 Chevy, a brand-new two-door post in black and white — This is the car Wes drove down to Galveston after reuniting with his first wife. Not long after hiring on at the shipyard and finding digs in a nearby boarding house, the wife left Wes for a notorious local gambler who was on his way to Vegas, and she took Wes’s car with her.

Model A roadster — The first of many hotrods Wes ever built, in 1948, while taking care of his family. He never went out in the evenings — he couldn’t afford to — and so stayed home nights and worked on “the rod,” which, once finished, reached speeds in excess of 120 mph.

1947 Fleetline Chevy — After his first wife split, Wes, still in Galveston, took up with another woman, to whom he concedes that he wasn’t always faithful. Apparently word of Wes’s dallying reached the woman. The next day at work a man who’d bumped into the woman earlier that morning, warned Wes: ‘Man, she’s looking for you. She’s going to cut your guts out.’ Well, that decided Wes. He bought this car on the quick and fled to the far reaches of the Louisiana bayou, where he hooked up with “an Indian from Oklahoma” and the two became crewmates of an offshore rig.

1955 Ford V8 — Or maybe this is the car he drove down to the Gulf with the Indian. The Indian definitely took a nap in the backseat of this car at one point.

1952 Chevy with an oversized, custom-installed 400 Chrysler Imperial engine, which was eventually replaced with more manageable 318 V8 engine salvaged from an old Dodge truck — This is the car he eventually drove back to Kansas City, where he would remain for most of his life, before eventually — after divorcing his third wife — moving on his own into a single-wide trailer in Neosho Falls in 1993.

Chevy Colorado pickup truck — He was in this car, in October 2011 — on his way to Downstream Casino with friends — when he fell violently ill. He was rushed to the nearest hospital, in Iola. A blood vessel had ruptured and he was bleeding internally. He was sent to Olathe, where he remained in the hospital for 14 days. He is certain, to this day, that the incident is related to a botched colonoscopy he received earlier that year (“I felt every goddamn twist and turn they made. Hell, I think they poked a hole in me up there.”) Other than a quadruple bypass in 2009, Wes is in good health and has plans to live as long as his former RN, who passed away in 2013 at the age of 101.

An ambulance — “Ever rode in an ambulance?” asked Wes, recalling that October day in 2011 when he was hustled from Iola to Olathe. “They are the roughest-riding damn things that I ever rode in. It seems like they could make those things a little bit smoother. It’s the same way with a school bus.”

IT WON’T surprise anyone who’s ever seen Wes at work in his shop, to hear that the higher-ups at Colgate-Palmolive asked the master machinist to come back to the factory, where he would remain until his retirement nearly 30 years later.

NELLIE Jane Carroll died of bone cancer in 1975. She was 74 years old. “She was a wonderful woman,” recalled Wes. “Mom had hair clear down to her butt just about, and always wore it in braids up around her head.”

But with the death of Nellie Jane, the question now arose: Who will care for Joe? Joe Carroll was the youngest of the nine siblings. He had Down syndrome and required round-the-clock care.

Last Monday, Gene sat thumbing through a photo album. He pointed to a series of family photographs. Group pictures. The Carrolls as kids. The Carrolls in middle age. “See, Joe was always in front. He was the baby. Oh, we spoiled that kid rotten. My mom had a big front room like this, and he would take bottle caps and place them in a row all over that front room. And that was his men. And we did not disturb that. You did not walk into that room, because, man, he’d get mad. Mom wouldn’t even go in there. I bet he had thousands of bottle caps. We all saved our bottle caps for Joe. And we didn’t disturb him when he was with his men. He passed a few years ago when he was 59 years old. But we spoiled the hell out of that kid. Joseph Warren Carroll!”

In the end, it was Wes who took Joe in after their mother died. “Mom always wanted Joe to go before she did, because they kept wanting to put Joe in that home down in Parsons. She said, ‘No way.’ Hell, everybody loved Joe.”

“But it was you who looked after him,” I said.

“Oh, well hell,” said Wes, “the other guys had families and everything like that. I don’t have any kids of my own. I told mom, ‘You don’t worry about Joe. I will take care of Joe. And I did.”

NOT LONG AFTER moving in with Wes, Joe began working at TriKo Inc. and at Tri-Valley, area agencies whose shared mission is to help individuals with developmental disabilities learn workforce skills. Wes soon took an interest in Joe’s progress at these places. Then he became interested in the places themselves.

There is another article to be written about the panoply of things Wes has created in his shop over the years. A Leonardo of the lathe, a da Vinci of the die cut, Wes Carroll, by some alchemy of imagination and metal, is able to transmute the everyday items of life — a bicycle wheel, a piece of wire, a sheet of tin — into objects of equal wonder and practicality. (He’s designed and built everything from a hydraulic horseshoe bender to a bowling ball cannon. He built the six-foot grill on which the world record for pancake flipping was set; a collapsible, off-road wheelchair from the parts of four used bikes for a handicapped marathoner; a pecan picker-upper; a hundred other things.)

But during the years that Joe was in his care Wes turned his efforts toward the creation of tools that individuals like his younger brother could use in the course of their labors. He custom built user-friendly wire cutters that are still being used at TriKo. And an easily-triggered analog counter, for employees whose addition skills are lacking. He made a press to create the plastic hat racks that Tri-Ko turns out by the hundreds. And he did it for free. “Hell, it’s just something to do,” said Wes.

IN 1997, InterHab, the state’s largest organization devoted to improving the lives of people with disabilities, presented Wes with their President’s Award, given “to an individual who has responded to the needs of individuals with disabilities.”

They put Wes and Joe up in the Hyatt Regency, in Wichita, on the 16th floor, and, on the day of the conference, invited Wes to stand on stage in front of 5,000 people while the president of InterHab made his remarks.

He called Wes “a man with the creativity of an artist, the energy of a teenager, the handshake of a blacksmith and the sensitivity of a new mother.” Then he handed Wes a large plaque.

Embedded in the plaque, behind glass, was a painting done by one of InterHab’s clients. It was an abstract; a kaleidoscope of smudges and swirls. “Some gal come up and says, ‘You know something? Those things are worth $500.’ I said, ‘Bullshit.’ ‘Oh, yeah,’ she said. ‘Would you take $500?’ she says. I says, ‘No, ma’am.’ I says, ‘I won’t never take no money for that.’”

“HOW IS it living so close to your brother all these years?” I ask Gene.

“I hate his guts,” Gene jokes. “And he hates mine.”

“They worry about me more than I worry about them,” says Wes.

“We worry about him because there’s two of us. There’s only one of him. If we see the light on over there, it’s OK. See the door open, it’s OK. If we don’t see him for a couple of days, we call.”

This article appeared originally in The Iola Register on November 25, 2017. *